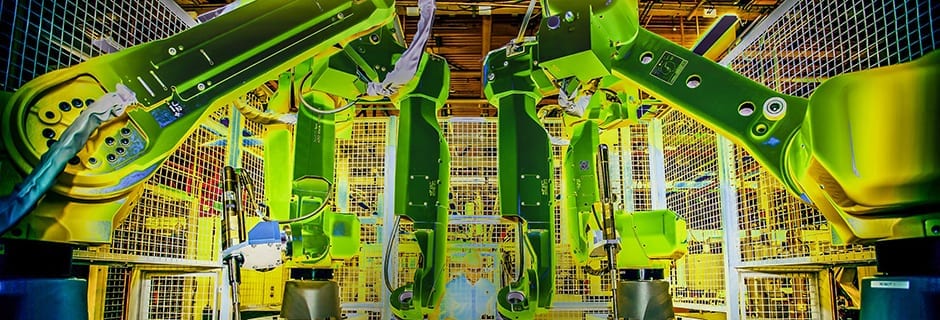

Above: Robotic Sump Assembly, taken by Steve Watts at Cummins Darlington, shortlisted in the amateur category of the EEF Photography Competition 2016

[title size=”4″]The government put a lot of flesh on the bones of its Industrial Strategy in November, with the announcement of a series of specific ‘sector deals’ and a set of four ‘grand challenges’. The challenge to the UK economy is productivity; while the Industrial Strategy specifies clear targets for R&D investment, how far will this help? James Hurley reports.[/title]

To those of a certain age, the words ‘industrial strategy’ will conjure memories of state intervention propping up failing industries and stiffing competition by “picking winners”

Tony Benn Credit: Shutterstock.com

In 1975, Tony Benn outlined his vision for a decade-long

Margaret Thatcher Credit: Shutterstock.com

industrial strategy, yet by the mid 1980s unfettered free markets were all the rage and the creed of interventionism was on the scrap heap along with British Leyland.

In November, as Theresa May outlined her government’s approach to what she called a “modern industrial strategy”, it must have felt to some like we’d come full circle.

The Prime Minister spoke of “a new approach to how government and business can work together to shape a stronger, fairer economy”. “At its heart it epitomises my belief in a strong and strategic state that intervenes decisively wherever it can make a difference,” she said.

While the debate over to what extent the government can and should be guiding the free market’s invisible hand will rage on, it is notable that there is no shortage of support these days across the political spectrum for the basic principle that the state could do more to improve areas such as skills and helping commercialise Britain’s world class science.

What’s less clear is how successful the ideas presented in November’s 255-page industrial strategy white paper will be. Below, the key ideas are outlined along with reaction from industrialists, entrepreneurs and academics.

[title size=”2″]The goals[/title]

Underpinning every idea, scheme and investment commitment in the white paper is the acknowledgement that something must be done to tackle Britain’s woeful productivity performance. Philip Hammond, the Chancellor, illustrated the scale of the problem at last year’s Autumn Statement: “It takes a German worker four days to produce what we make in five, which means, in turn, that too many British workers work longer hours for lower pay than their counterparts.”

This British productivity gap is well known but “shocking” nonetheless, he said. The issue is making the nation poorer by contributing to stagnant wage growth and falling living standards. If productivity could be improved, living standards would rise because it means the quantity and standard of work improves without any increase in ‘inputs’, i.e. labour and materials. Related problems which must be solved include Britain’s weak overseas trading record, a chronic lack of investment by our companies in skills and technology, and an over-reliance on London and its financial services powerhouse.

Outrigger robot, taken by Alison Bulto-Dowd at Dura, shortlisted in the amateur category of the EEF Photography Competition 2016

That’s the basic theory, so how does the government propose setting about the enormous task? The big picture was easy enough to ascertain from the white paper. The government believes it can do more by backing four key sectors of the economy; the construction and auto- motive industries; investment in artificial intelligence (AI) and life sciences. All four are to get so called “sector deals”, which are targeted partnerships between the state and the private sector. For example, 25 global organisations will get government backing to invest in life sciences in the UK.

GlaxoSmithKline will get £40 million to allow the drugmaker to expand its research on biological and genetic patient data that could lead to new treatments. British companies were also set “four grand challenges” to help the nation tackle the major hurdles it is due to face from our demographics and the rise of new technology: our ageing society, the management of the transition away from fossil fuels and towards a low carbon economy, the future of transportation, and artificial intelligence and the “data economy”. There was cautious support for the core mission statement among the major industry groups, although most pointed out this blueprint will be quickly forgotten if there is no long term, cross-party support for the core ideas across successive parliaments. The independent Industrial Strategy Commission was among those arguing that a permanent body must be established to measure progress of the ideas contained in the document. The government said it wants to raise total research and development (R&D) investment to 2.4 per cent of GDP by 2027, but the EEF, the manufacturers’ body, wondered why targets were not set to try to measure whether the strategy is actually improving productivity or not.

[title size=”2″]The winners[/title]

Sectoral deals to raise productivity in construction, artificial intelligence, auto- motive and life sciences might provoke memories of “picking winners” but many see them as sensible goals. In construction, the government wants to reduce the environmental impact and improve the efficiency of building projects so housing and major infrastructure projects can be delivered more quickly and cost effectively. The industry employs almost one in ten of the UK workforce so the government believes it is a prime target for greater investment in innovation and skills and for boosting its export potential. £170 million will be provided to help the sector modernise construction technologies and develop associated skills and training programmes.

Utility Rov, taken by Mike Smith at Utility Rov Services, shortlisted in the professional category of the EEF Photography Competition 2016. This Utility Rov is used in the subsea energy industry for clearing areas of the seabed of boulders and debris to allow cables to be laid as well as similar functions

The UK is already a world leader in artificial intelligence (AI), for example producing Deep Mind, which now underpins Google’s AI strategy, and by one estimate it will add £232 billion to the UK economy by 2030. A government review has recommended a raft of support measures, including help for export and inward investment in UK AI companies, help for the rest of industry to apply AI innovations; the creation of an “AI Council” to promote growth and coordination in the sector; and the creation of 200 more PhD places in AI at leading UK universities, attracting candidates from diverse backgrounds and from around the world. Britain’s automotive sector employs 159,000 people directly in vehicle manufacturing, with an additional 238,000 in the supply chain, according to official figures. The government said it will provide support to help car makers build the next generation of ultra-low and zero-emission vehicles by supporting the development of agile supply chains and by helping to secure international investment. For example, the Government and industry have agreed to co-operate to invest £1 billion over the next decade in the Advanced Propulsion Centre to help the Coventry-based organisation to research, develop and commercialise the next generation of low carbon technologies. £3 million will be provided to set up the Automotive Investment Organisation to lead inward investors into the UK.

INVEST IN AI AND ROBOTICS TO RAISE PRODUCTIVITY

Juergen Maier, CEO, Siemens UK

Juergen Maier, chief executive of Siemens UK, said the overall strategy is a “good start”. “Through greater investment in R&D, and especially through the application of advanced industrial digital technologies like AI and robotics, we can support many more new and existing manufacturing industries – raising productivity and creating thousands of new highly skilled and well paid jobs. “But there is still a long way to go. We now need to understand the deliverables, and better support small manufacturing businesses to adopt advanced technologies at a faster pace.”

[title size=”2″]The missing[/title]

“Investment in new forms of energy is “dwarfed by the costs” of the contentious £20 billion nuclear plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset”

Picking winners inevitably means leaving others out. There was puzzlement in some quarters at the lack of emphasis on other areas of strategic importance, such as aerospace and food. Perhaps the former was viewed as already a success story of state and private sector collaboration, with existing investments in technology, supply chains and skills helping to produce a world class industry.

However, the food industry, the UK’s largest manufacturing sector and worth £28.2 billion to the economy every year, has been crying out for more support and had been hoping for its own sector deal. Malcolm Evans is an investor and industrialist, with interests ranging from digital start-ups to supporting early and growth-stage manufacturing businesses. He argued the sector-focused “cherry picking around artificial intelligence, auto- motive, construction and life sciences is a touch bizarre”. “One could easily say, for instance, that the food and enterprise software sectors are more under-lever- aged in terms of exploiting UK innovation and import substitution potential”.

Chris Wright, founder of Moixa

The food industry certainly believes more help could leave it well positioned to deliver a better export performance and higher productivity through adoption of automation. Despite a commitment to help the industry transform food production while reducing emissions, pollution, waste and soil erosion, the lack of emphasis on a sector that argues it will be most affected by Brexit looks to some like a strange oversight. Energy was another area where some felt there could have been greater commitments, despite a focus on areas such as helping to boost energy storage and electric vehicles. Chris Wright is co-founder of Moixa, a company which manufactures batteries for home energy storage, said to be a key to the nation’s future energy strategy. The company was name checked in the white paper for its involvement in a project aiming to transform the energy infrastructure of the Isles of Scilly. “Of course we applaud the emphasis on electric vehicles and battery technology, since these are vital to the energy transition that is underway, and at the moment the UK is woefully behind in this area,” he said. “However we still see no sign of a coherent energy policy that acknowledges the speed with which this sector is transitioning.” He said the investment in new forms of energy is “dwarfed by the costs” of the contentious £20 billion nuclear plant at Hinkley Point in Somerset, which is being funded by French and Chinese investors and locks British consumers into paying high prices for electricity for the next three decades. “Models such as peer-to-peer energy enabled by solar and storage have the potential to be transformative and low cost, and urgently need demonstrating at scale,” Mr Wright said.

DAVID BAILEY, ASTON BUSINESS SCHOOL

David Bailey, professor of industry at Aston Business School

David Bailey, professor of industry at Aston Business School, warned: “It’s doubtful if this effort really is enough to deal with the disruption Brexit may well bring – to inward investment for example – or to properly grasp the opportunities and challenges of the fourth industrial revolution.” David Bailey, professor of industry at Aston Business School

Malcolm Evans of UK Accelerator

MALCOLM EVANS, UK ACCELERATOR

Malcolm Evans is less convinced. He said the approach presented by the government was a “triumph of lists”. “It offers little concrete about broad scale capability or capacity, the areas in which the state can play a valid role. Malcolm Evans of UK Accelerator “An industrial strategy needs either to be about a commitment to serious long-term infrastructure, or massive capacity pump priming. The former could be the creation of nationwide highly-focused technology skills institutes as a major education provider. The latter might be real transformation of connectivity, both online and via local transport, or dynamic and realistic action on energy. “As a start-up and scale-up activist, I’d be tempted to say, “Thanks for the thoughts but I’ll stick to my day jobs rather than be dazzled by any of this rather turgid and detail-lite rhetoric.”

TONY HAGUE, PP CONTROL & AUTOMATION

Tony Hague, managing director of PP Control & Automation, a mid-sized manufacturing company, was more positive, welcoming the industrial

strategy as a vision statement. “It seems to focus on all of the areas that will help us improve our competitiveness, including emerging technologies, training and development and support for growth sectors,” he said “The UK is well placed right now to show ambition and the strategy has to successfully engage Government, academia and industry, especially the small and medium-sized companies that remain the lifeblood of our manufacturing base.” Mr Hague’s business is an outsourcer for automotive, aerospace and electronics manufacturers among others. He added: “My only concern is the ‘how’. It’s very easy to put a nice document together that says all the right things…I want to understand some of the detail behind the practical application and how it will be rolled out. “Most important of all, I want all the political parties to get behind the Industrial Strategy and not see it as an election bargaining chip.”

-Photo caption- Working Down T’Mill, taken by Mark Tomlinson at Liberty Steel in Stocksbridge, South Yorkshire, shortlisted in the Amateur category of the EEF Photography Competition 2017. This is the working environment of the modern steelworker. Video feeds and remote controls have overtaken dirty, noisy cabins and manual labour. This workstation handles primary rolling of material destined for high integrity aerospace applications.

[title size=”2″]Labour force reaction[/title]

Some unions fear that an industrial strategy that promotes automation could spell bad news for workers. More automation can help drive up productivity, but it might also mean fewer jobs. Tim Roache, GMB’s general secretary, warned that the wrong approach to bolstering productivity would mean “fewer jobs, more wealth concentrated in the hands of the richest and a route to even further casualisation of the workforce, much as we have seen with the likes of Uber – old fashioned exploitation in new digital clothes”. Mr Pearce noted that “the low-skilled, low-wage sectors in which millions of British people work” were generally overlooked in the white paper favour of a focus on “high value-added sectors”.

Working Down T’Mill, taken by Mark Tomlinson at Liberty Steel in Stocksbridge, South Yorkshire, shortlisted in the Amateur category of the EEF Photography Competition 2017. This is the working environment of the modern steelworker. Video feeds and remote controls have overtaken dirty, noisy cabins and manual labour. This workstation handles primary rolling of material destined for high integrity aerospace applications.

Made smarter

In October, the government published a review led by Juergen Maier, UK chief executive of Siemens, which sets out how British manufacturing can be revolutionised by adoption of so called “industrial digital technology”. This refers to the use of robotics, 3D printing, augmented and virtual reality and artificial intelligence to boost productivity in manufacturing. The government believes the adoption of such ‘IDT’ will be key to the success of its industrial strategy, as well as in smoothing the path away from traditional manufacturing approaches towards automation, which some fear could result in the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs. Prof. Maier said smarter use of technology could actually produce a net gain of 175,000 jobs over a decade, and add £455 billion to the value of UK manufacturing, if businesses are given support to bene t from automation.

His report predicts that 295,000 manufacturing jobs will go in the “fourth industrial revolution” but that there is the opportunity to create 370,000 well paid, skilled jobs in manufacturing and 100,000 more in IT, software and analytics. More widespread adoption of IDT across supply chains will be crucial if the target is to be met, which means helping and inspiring small and medium-sized companies to automate. The scale of the challenge is laid bare by the fact that the process is expected to involve updating the skills of one million workers.

[title size=”2″]Digital infrastructure[/title]

£1billion was pledged for digital infrastructure improvements was welcomed, but critics note that represents the equivalent of only £1.5million for each Parliamentary constituency, which may do little to close the gap in the nation’s broadband coverage with world leaders like South Korea. The investment will include £176 million for 5G and £200 million for local areas to encourage roll out of full-fibre networks.