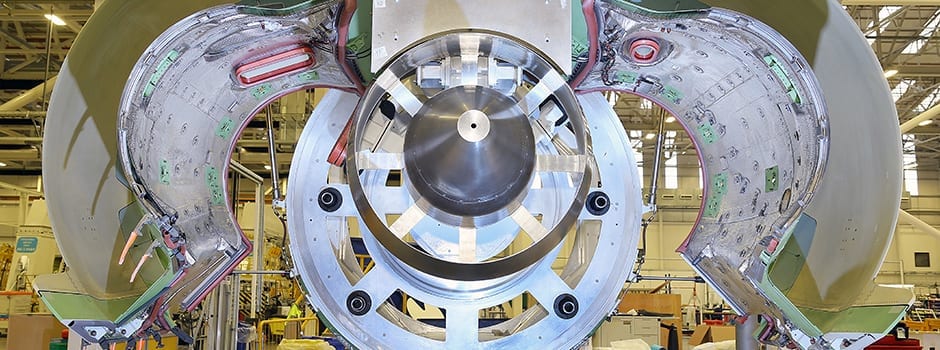

Above: Bombardier in Belfast. In October 2017 Airbus took a majority stake in the Bombardier C-Series programme, safeguarding 1,000 jobs. Airbus paid nothing for the stake, suggesting the programme has serious challenges (Credit: Bombardier)

[title size=”4″]Brexit poses major questions for manufacturing, but nowhere is the challenge more severe than in Northern Ireland, the only part of the UK to share a land border with the EU. By Gerrard Cowan[/title]

- Northern Ireland manufacturing jobs and exports are rising but slowly

- Belfast’s Bombardier had challenging year with US tariffs and Airbus intervention

- Brexit could bring opportunities, but food & drink sector is vulnerable

[/content_box] [/content_boxes]

[title size=”2″]An ideal world[/title]

Kelly said the ideal outcome would see Northern Ireland remain part of the customs union and single market, even if the rest of the UK exits, allowing frictionless trade to continue on the island of Ireland. He concedes there would then be a challenge over Northern Irish exports to the rest of the UK, should the latter be outside the single market and customs union. However, he said it should be possible to address this without placing additional administrative burdens or costs on business, he said.

Despite the challenges, Brexit could hold opportunities for the region, Kelly said, allowing it to act as a kind of bridge between the EU and the UK. No matter how it turns out, businesses need clarity, he said, with a need to agree a transition phase post-2019 being critical.

Beyond this, the sector would benefit from the return of the local Assembly and Executive, which have been suspended amid political negotiations.

“Our politicians were very good at jumping on aeroplanes and flying across the world and helping persuade potential investors to come here,” he said.

[content_boxes layout=”icon-on-side” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=”#fffccc”]

[content_box title=”RANDOX” icon=”” image=”” image_width=”300″ image_height=”200″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

Randox is investing £160 million in the Randox Science Park in Co Antrim (Credit: Randox)

Randox, one of the leading players in Northern Ireland’s life and health sciences industry, is scaling up its operations in the region.

Founded in 1982, it now employs almost 1,400 people in Northern Ireland, including 400 research scientists and engineers, said founder and Managing Director Dr. Peter Fitzgerald. It also has facilities in the Republic of Ireland, India, and the US.

As part of its upscaling, it has acquired an ex-Ministry of Defence site in Country Antrim, with 48 acres and over 400,000 square foot of buildings. The company is investing in £161 million in a project of renovation and regeneration as the Randox Science Park. A significant proportion of the laboratory development at the site has been completed, though work will continue for the foreseeable future.

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]

[title size=”2″]Transportation: buses, planes and tariff disputes[/title]

Credit: Bombardier

The biggest manufacturing sector in terms of economic output is engineering, Kelly said. Transportation is a particularly crucial dimension. Wrights Group, based in Ballymena, makes London’s new Routemaster buses. The region is perhaps best known, however, for aerospace; the world’s first aircraft manufacturer, Short Brothers, was established in the early 20th century, and was acquired from the UK government by Canada’s Bombardier in 1989.

Bombardier became the focus of an international row in the autumn when the US announced plans for tariffs on the company’s new C Series jet. There are fears the dispute could have a direct impact on jobs in Northern Ireland, where wings for the C Series are manufactured. Bombardier employs around 4,000 people in Belfast, and is the major customer for dozens of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) throughout the region. However, hopes for the project’s future were boosted in October, when Airbus signed an agreement to acquire a 50.01% stake in the C Series programme. Speaking at the time of the Airbus announcement, Michael Ryan, president of Bombardier Aerostructures and Engineering Services, said the agreement would strengthen the C Series on the international market, and “the resulting momentum will be felt positively in our business and throughout the Northern Ireland and UK supply chain”.

[fullwidth menu_anchor=”” backgroundcolor=”” backgroundimage=”https://ukmfgreview.com/2017/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2018/01/[email protected]” backgroundrepeat=”repeat” backgroundposition=”left top” backgroundattachment=”scroll” bordersize=”1px” bordercolor=”” paddingTop=”20px” paddingBottom=”20px”][title size=”2″]NORTHERN IRELAND DATA[/title]

[counters_box]

[counter_box value=”18.25″ unit=”bn £” unit_pos=”suffix”]Total sales of manufacturing companies in NI in 2016: £18,247 (NISRA BESES)[/counter_box]

[counter_box value=”18.25″ unit=”bn £” unit_pos=”suffix”]Total sales of manufacturing companies in NI in 2015: £18,247 (NISRA BESES)[/counter_box]

[counter_box value=”84120″ unit=”” unit_pos=”suffix”]Number of jobs in manufacturing sector in Q317 (NISRA QES)[/counter_box]

[counter_box value=”82590″ unit=”” unit_pos=”suffix”]Number of jobs in manufacturing sector in Q316 (NISRA QES)[/counter_box]

[counter_box value=”6.13″ unit=”bn £” unit_pos=”suffix”]NI Manufacturing exports in 2016 (NISRA BESES)[/counter_box]

[counter_box value=”5.81″ unit=”bn £” unit_pos=”suffix”]NI Manufacturing exports in 2015 (NISRA BESES)[/counter_box]

[/counters_box]

[/fullwidth]

[title size=”2″]Spreading its wings[/title]

The Airbus deal is “very good news, not just for Airbus and Bombardier but the entire supply chain”, said Leslie Orr, director of Aerospace, Defence, Security and Space (ADS) in Northern Ireland, who said there are about 70 companies in the region’s aerospace cluster that largely rely upon their business with the Canadian manufacturer.

One of ADS’ goals has been reducing the dependence of these companies on Bombardier, and getting more business outside Northern Ireland. In a 10-year strategy published in 2014, ‘Northern Ireland: Partnering for Growth’, ADS outlined a sales and marketing plan aimed at boosting the business that local companies get with companies like Airbus and Boeing.

There has been a high degree of success in this direction; Northern Irish SMEs now supply parts to other programmes around the world. A number of international aerospace and defence companies have invested in the region, too. Rockwell Collins, a US company specialising in avionics and information systems, in April 2017 acquired B/E Aerospace, another US company, which specialises in aircraft interiors and has facilities in the region. Orr said the major goal was attracting a ‘Tier 1’ integrator: a major component supplier to global manufacturers like Boeing or Airbus.

[content_boxes layout=”icon-on-side” iconcolor=”” circlecolor=”” circlebordercolor=”” backgroundcolor=”#fffccc”]

[content_box title=”SEAGATE” icon=”” image=”” image_width=”300″ image_height=”200″ link=”” linktarget=”_self” linktext=”” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″]

Seagate Factory, Derry.

(Credit: Lorcan Doherty)

About a quarter of the world’s computers contain a critical component made by Seagate Technology in the City of Derry/Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

Seagate was established in the city in 1993, and employs about 1,400 people at its site in the Springtown area. Its focus is manufacturing ‘recording heads’, tiny components of magnetic hard drives that read data from and write to the disk. The site produces about a million of the devices every day, which are then sent to the US company’s facilities in Thailand for assembly.

Over the past five years the site has sought to grow its research arm to complement its volume manufacturing focus, said Damien Gallagher, executive director of engineering; about 100 members of its staff now have a PhD. Seagate works closely with local universities, including Queen’s University, Belfast, where it supports a doctoral training programme that focuses on data storage.

‘We look to that as one source of the highly qualified engineers and scientists that will drive future development of the Springtown site.’

[/content_box]

[/content_boxes]

[title size=”2″]Food and Drink[/title]

Brian and Niall Irwin, Irwins Bakery.

While engineering is the region’s largest manufacturing sector by economic impact, the most important in terms of employment is the food industry. About 21,000 people work directly in the area, with another 78,000 employed in farming and support services, according to the Northern Irish Food and Drink Associa- tion (NIFDA).

The vast majority of sales are outside Northern Ireland, said Brian Irwin, vice chairman of NIFDA and chairman of Irwin’s Bakery. The industry saw sales of about £4.8 billion in 2016. Only about a quarter of this was sold locally, with over £2 billion going to Great Britain, £1.149 billion to the EU (mainly the Republic of Ireland), and £140 million to the rest of the world. Irwin’s own company sells about half of its bread products outside of Northern Ireland, he said.

Some of the challenges facing the food sector are common across the UK, labour supply being prominent among them; fruit growers have been particularly reliant on migrant EU workers. Some are already deciding not to come to Northern Ireland, he said, due to the uncertainty surrounding their place in the workforce and the fall in the value of the pound.

[title size=”2″]Complex infrastructure[/title]

The industry is part of a complex, all-island supply chain, developed over the past thirty years. About a quarter of Northern Irish milk, for example, is sent across the border to be turned into cheese, infant formula and other products. And it is not simply a north-south supply chain; many products – such as beef – are also sent to the rest of the UK to be processed.

“Nobody in their right mind wants to affect that, as it would hurt a lot of producers in Ireland, north and south,” Irwin said. “But it would also hurt consumers in GB, who currently enjoy a lot of very good beef and cheese and other produce from Ireland.”

After Brexit, the UK will be able to set its own standards in these areas and could even begin to diverge from the EU. Under this scenario, the food sector will still be subject to stringent controls over production, regulating the conditions under which animals are raised and produce is processed.

[title size=”2″]Brexit neutrality[/title]

There is an infrastructure in place that could be adapted to make cross-border trade as frictionless as possible: for example, the chief vets both North and South already cooperate on the control of animals on an all-Ireland basis. The EU’s Trade Control & Expert System (TRACES) could perhaps be extended and adapted. More broadly, a complex and intense system of collaboration could be established to see where the EU and UK could cross-adopt one another’s regulations.

The industry will also explore Brexit-related opportunities, Irwin said, such as increased exports to non-EU countries. There could also be the potential to restructure the sector if, for example, it becomes too onerous to send Northern Irish milk to a Southern Irish cheese factory; such facilities could instead be built in the North. In the meantime, the industry should look to “Brexit neutral” investments in, for example, new products, training staff, and research.

“Industry is used to uncertainty, but uncertainty at this level makes investment and forward planning very difficult,” Irwin concludes.