The UK’s space industry is the unsung hero of the country’s manufacturing. It is a world leader in small satellites and is now driving hard for a share of the lowcost launcher market.

BY MALCOlM WHEATLEY

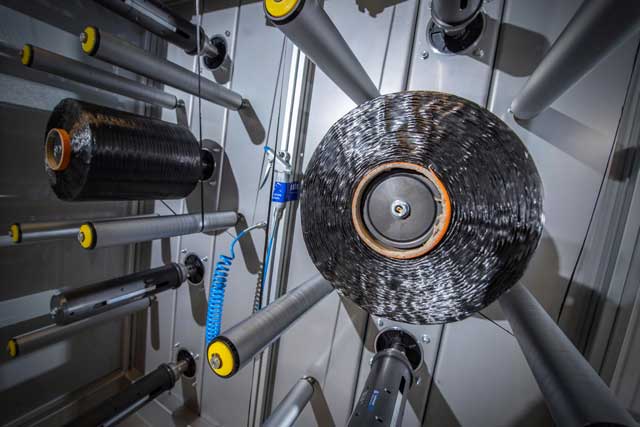

Look closely, and several things make that remarkable performance possible. First, the Orbex Prime is designed to be 30% lighter than similarly-sized rockets, thanks to its carbon fibre construction. Inside the Forres factory is one of the largest carbon fibre winding machines in Europe: an 18metre long behemoth that automates the rapid weaving of the intricate mixes of materials that make up the main rocket structures.

- Orbex’ factory in Forres, Scotland, houses one the largest carbon-fibre winding machines in Europe.

The rocket engines are equally innovative, using 3D printing to create what are currently the world’s largest singlepiece 3D printed rocket engines. Burning renewably-generated bio-propane, and generating roughly 90% fewer carbon emissions than SpaceX’s liquid kerosene engines, the engines can accelerate the Orbex Prime from 0 to 1,330 km/h in just 60 seconds. Already, Orbex has secured multiple commercial agreements to launch small satellites into orbit. These include agreements with Surrey Satellite Technology (SSTL), the world’s leading manufacturer of small satellites, and Astrocast, which is building a planetwide Internet of Things network.

“Our goal is to make smaller, more efficient launch vehicles, with a tiny CO2 footprint and zero orbital debris,” says Chris Larmour, Orbex’ chief executive. “We want to eliminate waiting time by launching on a regular timetable, with massively reduced costs and a more agile, modular approach. We can only do that by rethinking how we do it, rather than copying the past.”

Space in context

Britain’s space industry is something of an unsung success story. If people think of it at all, they think of companies such as Stevenage-based satellite and space probe manufacturer Airbus Defence and Space, which as well as designing and manufacturing satellites for telecommunications, earth observation, and science programmes, built the European Space Agency’s Rosetta deep-space probe, which made a historic rendezvous with comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in 2014.

Less well known are companies such as Guildford-based SSTL—originally a spin-off from the University of Surrey, now owned by Airbus—and Chelmsford- based Teledyne e2v. SSTL pioneered the manufacture of small satellites, and has launched over 60 since the company’s inception in 1981. For its part, Teledyne e2v built the imaging technology that provides the crucial multi-spectrum ‘cameras’ on board missions such as NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the Mars Reconnaissance Rover, and the European Space Agency’s Rosetta probe.

- SSTL’s Deployable Space Telescope, jointly developed with Surrey Space Centre & University of Oxford, showing the telescope stowed and deployed (L & R respectively)

- Caption: Surrey Satellite Technology’s Space Operations Centre.

But in fact, according to the 2018 edition of the UK Space agency’s The Size and Health of the UK Space Industry report, the 948 organisations that make up the UK’s space industry contribute almost £16 billion a year to the UK economy, and directly employ 42,000 people, with a further 80,000 jobs in its various supply chains. By 2030, government plans call for the industry to be roughly 10% of the global space economy, which currently stands at US$350bn. Moreover, the government is backing that ambition with hard cash in the form of development capital and assistance, including setting up the UK Space Agency, the Satellite Applications Catapult, and the UK National Satellite Test Facility.

Underpinning that effort are a number of space-centric ‘hubs’ or clusters. Glasgow, for instance, is at the heart of Scotland’s space industry, and homve to firms such as Alba Orbital and CubeSat manufacturer Clyde Space. Remarkably, according to the Scottish Centre of Excellence in Satellite Applications, the city designs and builds more satellites than any other city in Europe.

Further south, Oxfordshire’s Harwell Science and Innovation Campus reckons to be the largest space cluster in Europe, home to 94 space industry organisations, including the Satellite Applications Catapult, microsatellite antennae manufacturer Oxford Space Systems, research organisation RAL Space, and—from 2021—the UK National Satellite Test Facility. Close links with the government- funded Local Enterprise Partnership, OxLEP, help to nurture the burgeoning cluster, attracting businesses from across the globe to locate in Oxfordshire. “Five years ago,” says Catherine Hamelin of the Satellite Applications Catapult, “there were only five space industry organisations at the Harwell site; now there are over 90.”

Nanosatellites are as small as smartphones and often intended to operate in ‘clusters’. They are light and much cheaper to launch than traditional space communications hardware.

As with Scotland, local links also underpin the ongoing development of the UK’s two spaceports—the site in Scotland, and Spaceport Cornwall, which should see satellite-carrying rockets launched horizontally from underneath a Virgin Orbit-owned Boeing 747, operating out of Newquay Airport, which has one of the longest runways in the UK. CIoS LEP, the local enterprise partnership, again sees a space industry cluster developing in the county, and is working closely with the nascent spaceport and the nearby Goonhilly Earth Station, reckoned to be the largest satellite-receiving earth station in the world.

Reach for the skies

Three separate factors are driving the growth of the space sector in the UK. “First,” notes Orbex’ Larmour, “satellites are rapidly reducing in size, making them easier and cheaper to launch into orbit, and faster and cheaper to build. And when a satellite’s weight is measured in just tens of kilos—or even less—it becomes much easier for the private sector to get involved in building and launching them.”

So-called nanosatellites —as manufactured by Glasgow’s Alba Orbital and Clyde Space—are lightweight and tiny, and often intended to operate in clusters, or ‘constellations’. The CubeSat, for instance, is roughly a 10cm cube, weighing no more than 1.33kg. Many such microsatellites can be deployed on a conventional launcher, further reducing the cost of getting into orbit.

“People hold up SpaceX and Blue Origin as examples of private sector space involvement, but they’re actually the exception, with an ability to deliver multi-tonne payloads to orbit,” he points out. “Look at satellites weighing tens of kilos or less, and there’s a huge market for launches.”

Artist’s impression of the UK’s first commercial spaceport at the Sutherland Site in Melness, near Tongue, Scotland, which will conduct the UK’s first vertical, orbital rocket launch in the early 2020s. The team developing the spaceport is being led by Highlands & Islands Enterprise, with strategic support from Lockheed Martin.

Secondly, there’s the so-called ‘New Space’ phenomenon. Traditionally, going into space has been the job of central government, and agencies such as America’s NASA and the European Space Agency. The private sector built the satellites, launchers, and landers—but the purse strings were held by central government. No longer: pioneered by Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, the private sector is now directly going into space on its own account, as amply evidenced by Orbex and Virgin Orbit.

And third, with the passing of the Space Industry Act 2018— described as the most modern piece of space industry legislation in the world—the UK has put in place a regulatory framework underpinning the commercial exploitation of space from UK soil. A significant advance on the previous legislation—the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, to which over a hundred nations are now signatories—it places strict requirements on spaceports, launcher operators, and the bodies carrying out range control, notes Orbex’ Larmour.

“The space environment is becoming congested and contested,” says Christopher Newman, professor of space law and policy at Northumbria University. “A solid governance framework provides the protections that corporations, government, and investors all require.” Finally, what of Brexit? If Bridgendbased laser wire marking equipment manufacturer Spectrum Technologies— whose equipment was central to NASA’s Mars Insight lander, which landed on the Red Planet in November—is anything to go by, Brexit is an irrelevance.

“There’ll be some adjustments to make, but for us, Brexit won’t make any real difference at all,” says chief executive Peter Dickinson. “Even with worst-case WTO tariffs, the pound has already depreciated much more than that, anyway.

THE UK’S SPACE INDUSTRY GOES GLOBAL

A UK-Australia political declaration signed on 24 September 2019 launched a ‘Space Bridge’ between the UK and Australia—a platform to enable closer and stronger collaboration on space technologies and satellite applications, delivering benefits to the space industries of both countries.

“The goal is to increase innovation, increase the UK space industry’s global access and exports, and—potentially—strengthen the post-Brexit UK-Australia Commonwealth relationship,” says Catherine Hamelin, Australian Space Venture portfolio director at the UK’s Satellite Applications Catapult.

It’s not exactly a partnership of equals: the UK’s space industry is well-established, while Australia’s is relatively new, with its national space agency created as recently as 2018. But the various UK government bodies involved in setting up the Bridge see clear benefits for the UK, says Hamelin.

“It’s about global access,” she says. “Australia has very good links with other Asia Pacific economies, providing UK companies with a good platform for growth, and lowering the barriers to entry. For its part, Australia is targeting the creation of 20,000 jobs over a 10-year period.”